SPANISH MATTERS

The RAE Introduces New Rule Changes to the Spanish Language

Tuesday 6 June 2023

By Don Pablo

Many a country has an official body which acts as the custodian of its language, setting the rules and making changes and additions.

In Germany Duden has the final say about matters to do with the German language.

In France the Académie Française tries to set the rules, in particular to protect le français from contamination by foreign words, but it rarely works – the French aren’t going to stop using the word le weekend, just because the Académie says so.

In Spain the Real Academia Española (RAE) says what’s what; from time to time changing the rules and approving new words and phrases.

In this article Don Pablo highlights the main changes that were introduced to castellano in 2022.

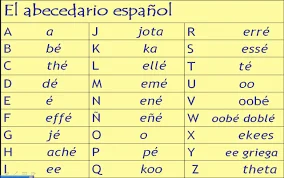

The RAE has recently announced some significant changes to the Spanish alphabet, much to the surprise of Spanish-speakers throughout the world (at the last count almost 600 million native speakers).

Disappearing letters

The letters “ch” and “ll” are to disappear as unique letters in their own right from the Spanish abecedario. This is on the grounds that they are digraphs, ie groups of two letters. So, from now on children in schools will be taught that the Spanish alphabet consists of just 27 letters (our 26 plus “ñ”).

The RAE points out that words containing these digraphs, such as chino, coche, llave and calle, will continue to be pronounced and spelt as before. Why make the change then?

Name changes

Some names of letters are to be changed:

“y” used to be called “y griega”. From now on it’s to be “ye”.

“i latina” will now be just “i”.

“b” will be “b” and “v” will be “uve” (I thought that was already the case!).

“w” will be “doble uve” instead of “doble u” (I thought it was “uve doble”, and so did all the Spanish speakers I know!).

New words and phrases

A number of new words and new uses of words have been approved, particularly in the fields of the new technologies, gastronomy, sex and gender and the Coronavirus. These include:

New technologies

bitcóin, bot, ciberacoso, ciberdelincuencia, criptomoneda, geolocalizar and webinario.

Gastronomy

sanjacobo, cachopo (típico de la gastronomía asturiana) paparajote (dulce murciano preparado a partir de la hoja del limonero) and el rebujito andaluz.

Also quinoa and crudité.

Tinto de verano (para referirse a la bebida típica de España compuesta de vino tinto y gaseosa o refresco de limón) and the addition of balsámico before vinagre.

Sex and gender

poliamor, transgénero, cisgénero and pansexualidad.

Pandemic

COVID, cubrebocas, hisopado and nasobuco, as well as new uses for terms such as cribado, burbuja social, nueva normalidad, triaje and vacunología.

***

The 2022 version of the digital DLE (Diccionario de la Lengua Española – official online dictionary of the Spanish language) incorporates a massive 3836 modifications. Blimey! I think I’ll just carry on as before …..Keep up the good work!

Hasta pronto.

© Don Pablo

***

Communion wafer, billy goat and other rude words – how to swear in Spanish

27 May 2023

By Don Pablo

Image: Courtesy of Wild Junket

Forget "swearing like a trooper", the real phrase should be "swearing like a Spaniard". Everyone in Spain, from sweet little kids to frail old ladies, peppers their everyday conversation with enough swear words to make a sailor blush. Here’s an analysis from Don Pablo.

In Spain, unlike in many other countries, references to toilet habits, male and female genitalia and other taboo subjects pop up in general conversations all the time, without anyone giving it a second thought.

Swearing in Spain is as common as it is ludicrous, so if you wish to embrace the ever-present potty language or simply want to understand what your Spanish friends are trying to say, read on!

Swear words in different cultures and/or language groups make a fascinating study in themselves.

For the Germans it’s all about the back passage, viz. Scheisse, Leck mich am Arsch, Arschloch, Du kannst mich mal ….. Connotations perhaps of homosexuality?

Image courtesy of Glitzertassen

The British, on the other hand, are more focused on the sexual act and the sexual organs, with cunt, twat, prick, dickhead, knobhead and the insults fucker, motherfucker, wanker and tosser.

The Americans like cocksucker, sonofabitch and suck my dick.

In Castilian Spanish - castellano, the language the andaluces don’t seem capable of speaking - the worst (best?) swear words all have to do with religion and blasphemy, ranging from communion wafer to shitting in the milk of the Virgin Mary to insulting some other Virgin, plus some that sound ridiculous to our ears, like billy goat.

Image courtesy of dePeru.com

There are so many different ways to swear in Spain, it’s hard to remember them all! Cursing is an integral part of the language, so it has become less taboo than in English. You hear it much more often and much more frequently than in the USA or England, say.

No one can ever argue that Spanish isn’t a colourful language.

And let’s be honest here, what’s one of the first things you do when you start studying a new language? You look up the bad words (palabrotas)!

As a starter, here are some of my favourites.

1. Me cago en la puta madre - This one takes the biscuit for one of the most hilarious and frightfully offensive swear words I have heard in Spain. Literally, it means “I shit on your whore of a mother”. I’d avoid using this, if I were you. You should use this phrase selectively and with caution. Remember, madres are sacred in Spain.

In fact, the “me cago en…” is one of the most common curse phrases you’ll hear in Spain. Whether you hear me cago en Dios “I shit on God”- that’s really bad - or me cago en la leche, literally “I shit in the milk (of the Virgin Mary)” but used more like “holy shit!”, there is no shortage of possibilities to be had with this one.

Try me cago en todos los santos or me cago en la Virgen del Pilar. Just remember if you want to insult anyone or anything in Spain, mention the mums or anything related to the Catholic Church and you’re good to go!

Interestingly, if you describe something as “de puta madre”, it means it’s bloody amazing!

2. Joder - Joder is about as common in Spanish as “ok” is in English. You hear it all the time. Loosely translated as “fuck,” it is nowhere near as strong. To soften it, many younger people say jooo-er and do not pronounce the “d”. That of course doesn’t stop the adults. I knew a Spanish teacher who loved to scream “Joooooder, ¿por qué no te callas?” (Fucking hell, why don’t you just shut up?) at the students in class.

It was hilarious and a little bit frightening, but that’s the Spanish public education system for you.

3. Gilipollas - Gilipollas is the equivalent of our “tosser” or “wanker”. The phrase "no seas gilipollas" is more or less the same as “Don’t be a twat!”

Photo: Courtesy La Tostadora

4. La hostia - La hostia means “the host,” ie the communion wafer. Spain being a predominantly Roman Catholic country, one of the worst and most common ways to curse is to somehow incorporate the holy mother church.

Hostia or hostias can mean many different things, like “shit” or “bloody hell” usually an exclamation all on its own, like something you can’t believe.

"Eres la hostia" means “you’re the bee’s knees,” in a good way or "hostia puta" “holy fuck.” Don’t forget you can always say, "me cago en la hostia", “I shit on the host.” Yikes, that’s blasphemous, so maybe not!

Walking along in San Sebastián many years ago with my rather hefty Irish girlfriend of the time, a guy coming towards us said to his mate “Qué gorda, la hostia”, “Fuck me, what a fatso”. Before I could work out what they’d said and react accordingly, they’d disappeared up a side street.

5. Que te folle un pez - This one is one of my favourites and one I have personally never said because I am terrified of using it wrongly. I think it sounds just plain ridiculous coming from a “guiri”. "Que te folle un pez" basically means “I hope you get fucked by a fish.”

Image courtesy of BuzzFeed

See what I mean when I say Spanish is colourful? How do you even come close to insulting like that in English?! How do you even begin to compare “screw you” or “fuck you” to that?

6. Cojones - In Spanish they say “cojones sirven para todo,” and it’s true. Cojones is without a doubt the most versatile of all the Spanish curse words on this list; you can use it for just about anything. Normally, it means “balls,” ie testicles. “You’ve got balls (as in courage)”- "tienes cojones". “That bothers me” – "me toca los cojones" and my personal favourite, "estoy hasta los cojones" – “I can’t take it anymore, I’m up to my (eye) balls.”

7. Cabrón - For me cabrón has always meant “bastard,” or “cunt”. It’s a pretty bad word. Literally meaning “male or billy goat,” I most frequently hear it as "qué cabrón" or "qué cabrones" in plural. Use it for people who are evil, people who are assholes and deserve a good punch in the mouth.

According to the Urban Dictionary, “A good definition that would apply to all Spanish-speaking countries would be asshole-fucker-bitch.” Can’t top that even if I tried.

8. Que te den (por culo) - This one is sort of like “up yours.” Seriously, does anyone even say that anymore? Anyway, culo means “ass” so I think you can probably figure out what the rest of it means on your own. You can say just "que te den" or "que te den por culo", both meaning “fuck you.”

9. Coño - Coño, literally “cunt”, is the most inoffensive word you can imagine in Spanish. Used by frail old ladies, as well as priests, it’s just a filler word. It can mean “mate” in that annoying way Liverpudlians use it, yet it’s often thrown into a sentence as a sign of frustration. It is never an insult! For that, you need to use cabrón (see above).

10. Pollas en vinagre - I’m going to end with my all-time favourite swear word in Spanish. Readers, I present to you "pollas en vinagre" “dicks in vinegar!”

Photo courtesy of Twitter

Use it how you best see fit, for its exact meaning still eludes me! On second thoughts, maybe don’t use it –just in case!

© Don Pablo

***

28M, finde, porfa, cole y peques - Abbreviations in Spanish

22 May 2023

By Don Pablo

There are nearly 400 abbreviations approved by the Real Academia Española (RAE - oh, there's one!), and thousands of accepted ones. You can even invent your own if you follow the rules.Abbreviations are divided into four types. I would add a couple more categories, but I'll come to that later.

The four types of officially accepted abbreviations are:

- Abbreviations – eg Dr. for doctor, Sr. for señor.

- Symbols – eg m for metro (metre), kg for kilo, km for kilometro.

- Initialisms (Siglas) – DNI – documento nacional de identidad (identity card)

- Acronyms – ONU – Organización de Naciones Unidas (United Nations/UN)

Let's have a look in more detail.

1. Abbreviations

Proper abbreviations are sets of letters that together represent a word. They use either the initial part of the original word — edit. for editorial (publisher) – or a mixture of the initial and the final part –Avda. for Avenida (Avenue). They should always have a fullstop at the end or a forward slash (/), with some exceptions. For example: C/ – calle (street); Dra. – doctora. Other common examples are a. C. (antes de Cristo) – B.C. (before Christ); EE.UU. (Estados Unidos) – U.S.A. (United States of America); FF.CC. for ferrocarriles, ie railway.

2. Symbols

Symbols are abbreviations of words of scientific or technical origin. They have the same form internationally. They are written in lower case. Common examples are m (metro) – metre; d (dia) – day; kg (kilo) – kilogramme.

3. Acronyms

Acronyms are also shortened forms of words and formed by initials. They may be pronounced by syllable or as complete words. You should write them in capital letters. Common examples include RAE (Real Academia Española) – Royal Spanish Academy; and RENFE (Red Nacional de Ferrocarriles Españoles) – Spanish National Railway Network.

4. Initialisms

Initialisms are called siglas in Spanish. They’re Spanish abbreviations of words also formed by the first letter of the words they represent. They work as nouns and usually follow the grammar rules that apply to nouns. They do not end in a full stop. People tend to use siglas as acronyms, although La RAE does not accept it. Unlike acronyms, you shouldn’t pronounce siglas as complete words, but letter by letter, but do not be surprised to hear people disrespect this rule. You should also write them in capital letters.

Common examples are:

DNI (documento nacional de identidad) – ID; AVE (Alta Velocidad Española) – Spanish High Speed train and ONG (organización no gubernamental) – NGO (non-governmental organisation)

Photo courtesy El Mundo

*

Just as the Spanish have fallen in love with the roundabout over the last 20 years (even though they still haven't learned how to use them properly), so too they have become enamoured of abbreviations of words.

Look at the title of this article again. Time was, the Spanish were happy with fin de semana, por favor, colegio and pequeñ@s, but not any longer.

And they'd rather watch una peli than una pelicula or go to una disco rather than una discoteca.

So, abbreviations of common everyday words, by shortening them, is my 5th category.

My 6th category is dates.

28M is 28 de mayo, the date of the local elections in 2023.

Image courtesy of infolibre

11S is 11 de septiembre, ie 9/11, the date, in 2001, of the terrorist attack on the twin towers in New York, which caused the deaths of 2,996 people, including 2,977 victims and 19 hijackers who committed suicide.

11M is 11 de marzo de 2004, the date of the Madrid train bombings, when 193 people were killed and 2000 injured in Spain's worst ever terrorist atrocity and the worst in the whole of Europe since 1988.

That was the Lockerbie bombing when PAN AM flight 103 exploded above the Scottish town, killing all 259 on board and 11 on the ground.

*

So, that's my exploration of Spanish abbreviations. Here's a good little sentence to end with:

Despues de ver una peli e ir a una disco durante el finde, volvieron los peques al cole el lunes por la mañana.

© Don Pablo

Acknowledgements:

***

Those Little Things that Mean a Lot - the diminutive suffix

By don Pablo

Thursday 27 April 2023

Have you ever noticed that whenever you ask for something in a Spanish bar, restaurant or shop, the barman, waiter or shopkeeper invariably comes back at you with something a little different, as if they’re correcting you? Don’t be disheartened; they’re not. By adding a little something extra to the end of the word you’ve used, they’re just being friendly. They’re using the Spanish diminutive suffix, to give it its technical name.

Let’s look at some examples. In a bar, ask for una cerveza, una caña or un tubo and the barman, more often than not, will confirm your order with una cervecita, una cañita or un tubito. This doesn’t only apply to alcoholic drinks, of course; un zumo becomes un zumito, and un café, un cafelillo or un cafelito.

When asked to wait a moment, a minute or a second, you will be told un momentito/un momentillo, un minutito or un segundito. The nicest examples of this diminutive suffix I’ve come across recently are muy cerquita de aquí (very very near here) and ahora mismito (right away). And surely the most sublime example of the use of this linguistic feature is in the double diminutive chiquitita, as immortalised in the Abba song of that name.

The grammar is that, in theory, you can add the suffix –ito, -ita, -itos, -itas or –illo, -illa, -illos, -illas to any Spanish noun, the effect being to make the thing smaller, more familiar, more affectionate. Sometimes it doesn’t really change the meaning much at all!Some nouns with diminutive suffixes have become nouns in their own right, for example:

perro – dog; perrito – puppy; perrito caliente – hot dog

gato – cat; gatito – pussycat

pan – bread; panecillo – bread roll

cigarro – cigar, cigarette; cigarrillo - cigarette

amor – love; amorcito - darling

paseo – walk; paseíto – little stroll

bocadillo – sandwich

fresquito – nice and fresh

There are, of course, suffixes which make things bigger, but that’s the subject of another article…..

© Don Pablo

***

20 Countries Divided by the Same Language

Sunday, April 2, 2023

You’ve heard the one about the United Kingdom and the United States – two countries divided by the same language. That’s good; witty but true. Not only is the pronunciation quite different, but so is the spelling sometimes (, eg colour v color, honour v honor) and usage. The two versions of English, commonly known as Oxford (or BBC) English and American English, often have different words for the same thing, eg bonnet (of a car) v hood; boot v trunk; curtains v drapes; wardrobe v closet.

They say the same about Portuguese from Portugal and Portuguese in Brazil; also French and Canadian French or Quebequois.

Well, I have to tell you that it’s also similar in the Spanish-speaking world. There are 20 countries or territories around the world where Spanish is the official or de facto language, testament to the success of Spain as a colonial power.

Pronunciation usage and vocabulary vary from country to country. In many isolated areas, the Spanish spoken is closer to the original Spanish spoken by the conquistadores than to modern-day castellano. In others, local languages have had a direct influence on the Spanish they inherited from the colonial invaders.

One word which highlights this difference rather well is tortilla. In Spain this is an omelette; in Central America and Mexico it’s a flat maize pancake. In colloquial usage it can mean lesbian sex and a prostitute.

Countries Where Spanish is an Official Language

There are 19 countries other than Spain where Spanish is an official or de facto language. In fact, Spanish has the largest number of native speakers besides Mandarin Chinese. With 380 million native speakers, Spanish surprisingly surpasses even English for the number of native speakers, to the tune of over 100 million.

Background

Spain sought to expand its influence into the New World after Christopher Columbus discovered it in 1492. The conquistadores headed to America, as did the other great colonial nations of the time, like the Dutch, English and Portuguese. But Spain was more successful, which is partly why all but five countries in South and Central America speak Spanish, the exceptions being Belize (English), Brazil (Portuguese), French Guinea (French), Guyana (English) and Surinam (Dutch).

The 20 countries

Let’s take a look at the 20 countries that have Spanish as an official or de facto language. They are organised by continents and regions.

Africa

Equatorial Guinea- a small country in central Africa, this country is named for its location on the Equator.

Caribbean Sea

Cuba - island that sits where the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean meet.

Dominican Republic - on an island shared with Haiti (French-speaking).The original name of the island was Hispaniola.

Puerto Rico - territory owned by the United States, both English and Spanish are official languages.

Central America

Costa Rica - means "rich coast" due to the amount of gold jewellery worn by the natives when discovered by Christopher Columbus.

El Salvador - means "the Saviour”, ie Jesus Christ.

Guatemala - largest population in Central America.

Honduras - means "depths". The country has a high poverty index.

Nicaragua - Spanish is the de facto language. It is the largest Central American country by area.

Panamá - bridge between Central and South America, broke away from Colombia with the help of the United States Army, which then oversaw the completion of the Panama Canal.

Belize - formerly British Honduras, does not recognise Spanish as its official language, yet it is the de facto language, but it is not officially recognized by the government as the official language of Belize, which remains English.

Europe

Spain - country where Spanish originated that colonised all other future Spanish-speaking countries

North America

Mexico - the 13th largest country in the world by area, has over 126 million inhabitants, Spanish is the de facto language.

South America

Argentina - Spanish is the de facto language. It is the largest Spanish-speaking country by area.

Bolivia - has two capitals, a constitutional one (Sucre) and an executive one (La Paz).

Chile - Spanish is the de facto language. It is a long strip of land with the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Colombia - second only to Brazil in its level of biodiversity, it is categorised as a "megadiverse" country due to so much biodiversity.

Ecuador - named for its location on the Equator.

Paraguay - 90% of the population also speaks a dialect of Guaraní in addition to Spanish.

Perú - considered a megadiverse (biodiversity) country.

Uruguay - Spanish is the de facto language. Despite territorial disputes involving Spain and Portugal and Brazil and Argentina, Uruguay has remained independent.

Venezuela - one of the first countries to declare independence from Spain. Named after Venice in Italy.

***

There are a few other places where Spanish holds significant influence, such as Andorra in the Pyrenees between Spain and France, Gibraltar, on the southern tip of Spain, which belongs to the United Kingdom, and the United States, which is second only to Mexico when it comes to the number of native Spanish speakers.

A word or two on the Philippines, which was a Spanish colony for some four centuries. Spanish was the official language of the archipelago from the beginning of Spanish rule in the late 16th century, through the Philippine–American War (1899-1902) and subsequent colonisation by the USA and remained co-official after independence in 1946, along with Filipino and English, until 1973. Its status was initially removed in 1973 by a constitutional change, but after a few months it was re-designated an official language again by a presidential decree. Under the current constitution, Spanish is designated as an auxiliary or "optional and voluntary language". They used to say that the sun never set on the Spanish Empire. Now that it's empire is long gone, you could say that the sun never sets on a Spanish speaker.

© Don Pablo

Additional material courtesy of corelanguages.com, geology.com, Pinterest, Wikimedia Commons, Wikipedia, and World Maps.

***

The Three Big Problems in Learning Spanish

2. SER or ESTAR

"To be or not to be? That is the question".

By Don Pablo

Thursday, 30 March 2023

It is indeed the question. SER or ESTAR? Which to use? And when?In the second in his series of articles about particular difficulties encountered by English-speaking learners of Spanish, Don Pablo tackles the problem that is the verb "to be".

2. SER or ESTAR?

The two verbs for TO BE in Spanish are not interchangeable. So, when do you use SER and when ESTAR?

As a broad general rule, SER is used to describe permanent or inherent characteristics, whereas ESTAR is used to indicate a temporary, transient or accidental state and position or location. Let’s be more specific and look at some examples:

El hielo es frío.

El azúcar es dulce.

Ese hombre es muy grande.

Estas flores son muy bonitas.

BUT

Esta sopa está muy fría.

Mi café está muy dulce.

Las patatas fritas están muy calientes.

Compare:

La chica es muy guapa

.La chica está muy guapa hoy.

SER is also used:

a) to denote origin, ownership or the material from which something is made:

Sus padres son de Ronda. El coche es suyo.

La silla es de madera.

b) to indicate nationality, religion, rank and profession:

Es inglés.

Ella es católica.

Rubén es capitán.

Paco es carpintero.

c) when the predicate is a noun, pronoun or infinitive:

Mañana será otro día.

Algo es algo.

Trabajar bien es lo que importa.

d) with past participles to form the passive:

ser quemado vivoser declarado vencedor

El asesino fue condenado a muerte.

e) in impersonal expressions and expressions of time:

Es lógico que .....

Es evidente que .....

Ya son las once.

Es hora de cenar.

ESTAR is also used:

f) to indicate position:

Madrid está en el centro de España.

Tus amigos están en la playa.

"Estuvimos en el Bar Encuentro."

g) to form continuous tenses:

Está lloviendo a cántaros.

Los jóvenes están bailando.

h) some idiomatic expressions:

estar de acuerdo

Está bien.

¿A cuánto están las fresas?

***

Phew! Did you get all that?

¡Suerte!

© Don Pablo

Acknowledgements:

A Manual of Modern Spanish, Harmer & Norton (UTP 1935)

Advanced Spanish Course, K Mason (Pergamon 1967)

Tags: accidental, Don Pablo, donquijote.com, estar, expression, Harmer, idiomatic, impersonal, inherent, location, Mason, Norton, not to be, permanent, position, question, Spanish, Spanish Matters, temporary, time, to be, to be or not to be, transient

***

The Three Big Problems in Learning Spanish

1. POR or PARA

Monday, 20 March 2023

By Don Pablo

When I was studying for my degree in Spanish back in the late 1960s/early 1970s we were made aware of four quite major problems for English-speaking learners of this most widespread language in the world.Later, during my Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) course in 1973-4, I naturally had lectures in Spanish pedagogy, ie HOW to teach Spanish.The professor focused on the same four areas of usage which are deemed to be a problem for school pupils and students.What are these four issues?POR or PARA; SER or ESTAR; PRETERITE or IMPERFECT; and PERSONAL 'A'.Over the next few weeks, in a series of separate articles, I shall tackle each in turn and hope that my thoughts are helpful.

1. POR or PARA

First up is POR or PARA. Both can mean "for", although they also have other meanings.

In the "Old Testament" of Spanish learning, A MANUAL OF MODERN SPANISH by Harmer and Norton (UTP 1935), the authors devote a whole 18 pages to the matter.

The "New Testament", AN ESSENTIAL COURSE IN MODERN SPANISH by H Ramsden (Chambers Harrap 1959), takes a similar amount of space.

My own university lecturer, Ken Mason, published his ADVANCED SPANISH COURSE (Pergamon 1967), in which he needs six and a half pages. But the best analysis I have seen is by Eye On Spain blogger, mac75.

Therefore, I shan't attempt to better what mac75 wrote recently; I shall simply refer you to his article here:

https://www.eyeonspain.com/blogs/whosaidthat/22232/por-or-para.aspx

Keep listening and learning!

Tags: degree, Don Pablo, English-speaking, estar, Harmer, imperfect, mac75, Mason, Norton, para, personal 'a', por, Postgraduate Certificate in Education, PGCE, preterite, Ramsden, ser, Spanish

***

Top 10 Tips for Learning Spanish

Wednesday, November 17, 2021

So many of my foreign friends and acquaintances here in Spain desperately want to do something about improving their Spanish language skills.

Some have tried quite hard, but get quickly frustrated. So what can foreign immigrants do to improve their Spanish enough to carry on meaningful conversations with the locals?

As a former languages teacher, teacher trainer and UK schools inspector I have seen first hand what works and what doesn’t. Not just in the UK, but in Australia, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain, where I had the privilege to go on study visits. So, here are my top 10 tips (13, actually!).

- Enrol on a course – a free one, if possible – and attend the classes regularly. Did you know that the Junta de Andalucía provides funding to town halls for free Spanish lessons for foreigners? In Ronda, where I live, for example, my non-Spanish-speaking friends receive three mornings a week of free tuition.

- Find a Spaniard who will give you conversation practice in exchange for reciprocal conversation in English (your average Spaniard is desperate to improve their English). That way it doesn’t cost you anything. It's called intercambio.

- Buy a good course book which you can work through on your own.

- Carry a little notebook with you at all times to jot down new words and phrases for learning later.

- Get into the habit of learning new material every day, eg from the above mentioned notebook, or from the course book or homework from your teacher. That may sound like a chore, but, believe me, very few of us can just pick up a foreign language by osmosis, as it were, just because we happen to live in the country. Most of us have to make a lot of effort. Take my own case: a four-year university course which took me from zero knowledge to honours degree standard, followed by another 50-odd years of continual learning. Yes, I’m still learning. Although I live in Spain , I reckon I learn something new about the Spanish language every single day.

- Watch Spanish TV, especially the news and the soaps. Quiz shows are also good.

- Listen to the radio too – the standard of spoken Spanish there, especially on RNE (Radio Nacional de España) is pure castellano and of the highest quality.

- Read a newspaper regularly, though not La Vanguardia, ABC or El Mundo, as they can be rather turgid and dull. I like the style and language and content of El País, Sur and Málaga Hoy better from a language-learning point of view.

- Read children’s stories. Fairy tales, where the stories are familiar, are particularly suitable.

- Play language-learning tapes and/or CDs in the car and hone your pronunciation. Practice out loud! Nobody can hear you!

- If you have British TV,record and watch the BBC’s Spanish language-learning output, which has always been excellent.

- Buy a decent dictionary, nothing smaller than the biggest Collins or Larousse you can find.

- Take a Spanish lover, but check that it’s OK with your spouse or partner first!

But really, the secret, above anything else, is to “wallow in a bath of Spanish”, as I used to tell my students.

Listen actively and attentively to as much Spanish as you can, and then gradually begin to imitate and emulate what you hear. That’s, after all, how we learned our mother tongue.

¡Mucha suerte!

Note: Previous versions of this article were published at www.eyeonspain.com and www.secretserrania.com

***

False friends in Spanish and English

Thursday, January 19, 2023

By Don Pablo

Languages are categorised into families, depending on their origen. Romance languages, those descended from the Latin spoken by Roman legionaires during the Roman conquest and occupation of much of southern Europe, include Spanish, as well as French, Italian, Portuguese and Romanian.The Germanic family includes Dutch, Flemish, German and English, although English has many Latin-origin words as a result of the Norman (French) conquest of England in 1066 and the subsequent repopulation of many areas by Normans.As a result there are many words in English and Spanish which are the same or similar. These are called cognates.The problem is not all cognates have the same meaning. These are called false cognates or, more commonly, false friends or falsos amigos.

Cognates

Spanish and English have literally thousands of cognates, words that are basically the same in both languages, having the same etymology and similar meanings. 30% to 40% of all vocabulary in English have related words in Spanish.

Perfect Cognates

These are words which are spelt exactly the same in two languages and have the same meaning. Be careful – although the spelling may be the same, the pronunciation is often different.Examples in English and Spanish include:

- animal – animal

- chocolate – chocolate

- hotel – hotel

- simple – simple

Near Perfect Cognates

These are words which are very similar and have the same meaning, but the spelling is slightly different.Examples in English and Spanish include:

- attention – atención

- public – público

- religious – religioso

- delicious – delicioso

False Cognates/False Friends

There are, however, many word pairs that look like they might mean the same thing but don't. They can be confusing, and if you make the mistake of using them wrongly in speech or writing you're likely to be misunderstood.Following is a list of some of the most common false friends — some of the ones you're most likely to come across when reading or listening to Spanish:

- actual: This adjective (or its corresponding adverb, actualmente) indicates that something is current, at the present time. Thus, the day's hot topic might be referred to as un tema actual. If you wish to say something is “actual” (as opposed to imaginary), use real (which also can mean "royal") or verdadero.

- asistir: Means to attend or to be present. Asisto a la oficina cada día, I go to the office daily. To say "to assist," use ayudar, to help.

- atender: Means to serve or to take care of, to attend to. If you're talking about attending a meeting or a class, use asistir.

- boda: Means a wedding or wedding reception. A body (as of a person or animal) is most often cuerpo or tronco.

- campo: Means a field or thecountry(side). If you're going camping, you'll stay in a campamento or a camping.

- carpeta: Means a file folder (including on a computer) or a briefcase. "Carpet" is most often alfombra.

- compromiso: Meaning a promise, obligation, or commitment, it does not usually convey the sense that one has given up something to reach an agreement. There is no good noun equivalent in Spanish of "compromise".

- constiparse, constipación: In verb form, it means to catch a cold, while una constipación means a cold. Someone who is constipated is estreñido.

- contestar: It's a very common verb meaning to answer. To contest something, use contender.

- corresponder: Yes, it does mean to correspond, but only in the sense of to match. If you're talking about corresponding with someone, use a form of escribir con or mantener correspondencia.

- decepción, decepcionar: Means disappointment or to disappoint. To deceive someone is engañar a alguién. Something deceptive is engañoso.

- delito: This is an offence or a minorcrime. The feeling of delight can be un deleite, while the object that causes it is un encanto or una delicia.

- desgracia: In Spanish, this is little more than a mistake or misfortune. Something shameful is una vergüenza .

- despertar: This verb is usually used in the reflexive form, meaning to wake up (me despierto a las siete, I wake up at seven). If you're desperate, there's a true cognate you can use: desesperado.

- disgusto: Derived from the prefix dis- (meaning "not") and the root word gusto (meaning pleasure), this word refers simply to displeasure or misfortune. If you need to use a much stronger term akin to disgust, use asco.

- embarazada: Means pregnant, so be careful. Someone who feels embarrassed tiene vergüenza or se siente avergonzado.

- emocionante: Used to describe something that's thrilling or emotionally moving. To say emotional, the cognate emocional will do fine.

- en absoluto: This phrase means the opposite of what you think it might, meaning not at all or absolutely not. To say absolutely, use the cognate totalmente or completamente.

- éxito: Means a hit or a success. If you're looking for a way out, look for una salida.

- fábrica: That's a place where they fabricate items, namely a factory. Words for cloth include tejido and tela.

- insulación: This isn't even a word in Spanish (although you may hear it in Spanglish). If you want to say insulation, use aislamiento.

- ganga: It's a bargain. A gang is una pandilla.

- inconsecuente: This adjective refers to something that is contradictory. Something inconsequential is de poca importancia.

- introducir: This isn't truly a false cognate, for it can be translated as, among other things, to introduce in the sense of to bring in, to begin, to put, or to place. For example, se introdujo la ley en 1998, the law was introduced (put in effect) in 1998. But it's not the verb to use to introducesomeone. Use presentar.

- largo: When referring to size, it means long. Large, ie big, is grande.

- minorista: Means retail (adjective) or retailer. A minority is una minoría.

- molestar: The verb doesn't have sexual connotations in Spanish. It means simply to bother or to annoy. For the sexual meaning of to molest in English, use abusar sexualmente or some phrase that says more precisely what you mean.

- once: If you can count past 10, you know that once is the word for eleven. If something happens once, it happens una vez. By the way, la ONCE is the Spanish National Organisation for the Blind, which runs a daily lottery to raise funds.

- pretender: The Spanish verb doesn't have anything to do with faking it, only to try. To pretend, use fingir or simular.

- realizar, realizacón: realizar can be used reflexively to indicate something becoming real or becoming completed: Se realizó el rascacielos, the skyscraper was built. To realise as a mental event can be translated using darse cuenta (to realise), comprender (to understand) or saber (to know), among other possibilities, depending on the context.

- recordar: Means to remember or to remind. The verb to use when recording something depends on what you're recording. Possibilities include anotar or tomar nota for writing something down, or grabar for making an audio or video recording.

- revolver: As its form suggests, this is a verb, in this case meaning to turn over, to revolve, or otherwise to cause disorder. The Spanish word for a revolver is similar, but pronounced differently: un revólver.

- ropa: clothing, not rope. Rope is cuerda.

- sano: Usually means healthy. Someone who is sane or in his right mind is en su juicio.

- sensible: Usually means sensitive or capable of feeling. A sensible person or idea can be referred to as sensato or razonable.

- sopa: Soup, not soap. Soap is jabón.

- suceso: Merely an event or happening. A success is un éxito.

- tuna: Order this at a desert restaurant and you'll get edible cactus. The fish is atún.

For a complete list of false friends, click here.

Phew! Got all that?

The chances are you'll make a few mistakes, but just have a laugh about them and remember for the next time.

Acknowledgements:

www.letsspeakspanish.comwww.oxfordhousebcn.comwww.thoughtco.com

Note: A previous version of this article was published at www.eyeonspain.com

Tags: cognate, Don Pablo, Dutch, English, etymology, false cognate, false friend, falso amigo, Flemish, French, German, Germanic, Italian, language family, Latin, Near Perfect Cognate, perfect cognate, Portuguese, Roman, Romance Language, Romanian, Spanish, Spanish Matters

***

Spanish spelling and pronunciation

Monday, 6 March 2023

In this article Don Pablo takes a look at Spanish spelling and pronunciation.

Of course, the key to the successful development of our Spanish language skills is the ability to listen. This is, after all, how we began to learn our mother tongue, by hearing what was said to us by parents, relatives, friends and neighbours. If, as foreign language learners, we listen and imitate, not only will we begin to use the correct words and phrases in the correct way, at the right time and in the right place, we will also demonstrate more authentic pronunciation and develop more genuine accents.

One of the most important things to remember is that Spanish vowels are pure and unwavering, ie one sound, and always the same, unlike English, which is impossibly inconsistent and riddled with diphthongs. In English the same vowel may be pronounced in a range of different ways, for example, the vowel ‘a’:again (uh), small (aw), cap (ah), car (aahh), many (eh), paper (ay), and so on.Compare this with the absolute consistency of Spanish: pan, casa, cerveza, zanahoria.

The same applies to consonants; in Spanish consistent, in English not at all. The eminent linguistician, Simeon Potter, demonstrated the daft English spelling system by suggesting that ‘fish’ might be spelt ‘ghoti’ (‘gh’ from rough, ‘o’ from women and ‘ti’ from station!).

However, we digress…

As we have said, Spanish consonants, like vowels, are always pronounced consistently.

The only Spanish consonants which have different pronunciations are ‘c’ and ‘g’, yet these differences are defined by set rules which are logical and never change. Let’s have a look …

The letter ‘c’ is pronounced ‘k’ (hard) before a, o, u and any consonant, eg casa, copa, cubo, actriz, acción, sección. On the other hand, ‘c’ is pronounced ‘th’ (soft) before e or i, eg cerveza, excepto, cocina, acción, sección. Note the pronunciation of the ‘cc’ in the latter two examples above, ie ‘kth’ – ah-k-th-ee-on, seh-k-th-ee-on.

The rule is similar with the letter ‘g’. Before a, o, u and a consonant it is pronounced ‘g’ (hard), eg pagar, gol, agua, ignorancia. Before e or i ‘g’ is pronounced ‘ch’ (like ‘ch’ in Scottish ‘loch’). For example: generación, gira, agitar. To achieve a hard ‘g’ sound before e or i, a ‘u’ is inserted, as in guerra, guiri.

This rule takes a bit of getting used to, but if you listen out for examples and be aware of spellings, you should soon get the hang of it.

Other interesting points to note are:

- The Spanish alphabet had until recently 30 letters, the extra four being 'ñ', 'ch', 'll' and 'rr'. However, in 2022 the Real Academia Española (RAE) somewhat controversially changed this, by decreeing that the latter three are no longer letters in their own right.

- The letters ‘b’ and ‘v’ are virtually indistinguishable from each other, so much so that the occasional Spaniard is guilty of mis-spelling words by interchanging ‘b’ and ‘v’.

- There are no double consonants except ‘nn’ in words beginning with the prefix ‘in-‘, ‘cc’ as we saw above, and ‘ll’ and ‘rr’, which are separate letters in their own right.

Happy listening and hasta pronto.

Note: A previous version of this article was published at www.eyeonspain.com

***

The Languages of Spain

Friday, December 16, 2022

By Don Pablo

You may think that the language of Spain is Spanish. Well, it is of course. Officially known as castellano, Castilian Spanish, it is the equivalent of Oxford or BBC English in the UK or Hochdeutsch in Germany, ie the official, pure form of the language. In some countries this is “protected” by a body, eg the Real Academia Española in Spain, the Académie Française in France and Duden in Germany.

But, whilst castellano is the official language of Spain, there are other official languages too. Four in fact, although another two claim similar status. The four other official languages, viz catalán, euskera (Basque), gallego and valenciano. These are called regional languages.

Their use banned during the 40-year dictatorship of General Franco, since his death in 1975 and the subsequent and rapid democratisation of the country under Franco’s protégé, the since disgraced Juan Carlos I, the prohibited regional languages have been allowed to flourish. Euskera and catalán are the languages of officialdom and of instruction in schools in their regions. Basques and Catalans speak it as their mother tongue, only switching to castellano with reluctance. Catalunya wants to secede from Spain; the Basque country wants more independence. Valencia and Galicia are less “independista”.

Facts and figures

99 per cent of Spaniards speak castellano as their first or second language. Of the rest, eight percent of the population claim their first language to be catalán, four per cent valenciano, three per cent gallego and one per cent euskera.There are also dialects like andaluz, aragonés and zaragozano.

What is the difference between a language and a dialect? It’s difficult to define, but usually a language boasts its own body of literature. One commentator suggested a language is the speech of a country with an army, which isn’t strictly accurate, but you get the idea.

Scouse, Geordie and West Country are dialects or accents in the UK; Welsh, Scots Gaelic and Irish Gaelic are languages.

Which to learn?

If you’re a foreigner who lives in Spain or visits regularly, I would always recommend learning castellano, except maybe in Catalunya. However, catalán is not spoken widely throughout the world, whereas Spanish is a truly global language, nearly as important as English in world terms. With English and Spanish you can communicate pretty much everywhere on the planet.

Obviously, depending on where you live, you will inevitably pick up dialect words and phrases and to some extent pronunciation and intonation. But, that’s OK.

The important thing to realise is that you are extremely unlikely to pick up Spanish by osmosis. Of the very good foreign Spanish speakers I know around here, most have a degree in Spanish, were born here, have a Spanish parent, married a Spaniard, have a Spanish lover, or have lived here for a very long time. The rest need to work at it. And although it may sometimes seem like a struggle, it’ll be worth it in the end.

See my top ten tips for learning Spanish here.

Castellano or andaluz?

Andaluz has to be the worst dialect in Spain.

Even though I have an honours degree in Spanish (castellano), and have lived in the country for the best part of a decade and a half, I still struggle with the Andalusian dialect.

Mind you, I have a similar problem when I visit Baden-Württemberg in Germany with my German wife. Schwäbisch is arguably the most impenetrable of the German regional dialects.

I have an honours degree in German also, but in the country villages of this southern German Land (state), that’s not a help.

What to do? In Spain, I put myself about in local bars, I watch CanalSur or AndaluciaTV and listen to Radio Andalucía in the car. It helps ….. I’m getting there with andaluz!

© Don Pablo

Note: A previous version of this article was published at www.eyeonspain.com

Further reading:

The Rise and Fall of King Juan Carlos I (eyeonspain.com)

Tags: Académie Française, Andalucía, AndaluciaTV, Andalusia, andaluz, aragonés, Baden- Württemberg, Basque, BBC English, CanalSur, castellano, Catalan, catalán, degree, Don Pablo, Duden, euskera, France, Gaelic, gallego, General Franco, Geordie, German, Hochdeutsch, Irish Gaelic, Juan Carlos I, Oxford English, Radio Andalucía, Real Academia Española, Schwäbisch, Scots Gaelic, Scouse, Spain, Spanish, valenciano, Welsh, West Country, zaragozano