SPANISH HISTORY

This section is an unashamedly random collection of articles about historical aspects of Spain and its people. There is no chronology and no planned order of topics.

Despite the apparent haphazard nature of this section, I hope you find it interesting and informative.

***

20th Anniversary of 11-M – The Madrid Bombings

Monday, March 11, 2024

By The History Man

Today is the 20th anniversary of the 2004 Madrid train bombings (known in Spain as 11-M). In the morning rush hour of Thursday 11 March 2004 a series of coordinated, almost simultaneous bombings against the Cercanías (commuter train system) of Madrid hit the Spanish capital, killing 193 people and injuring around 2,050.

Overview

The bombings constituted the deadliest terrorist attack carried out in Spain's history and the deadliest in Europe since Lockerbie in 1988.

The attacks were carried out by individuals who opposed Spanish involvement in the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.

The atrocity took place three days before Spain’s general elections were scheduled.

Controversy about the handling and representation of the bombings by the government arose, with Spain's two main political parties—the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the Partido Popular (PP)—accusing each other of concealing or distorting evidence for electoral reasons.

In the elections, on Sunday 14 March, Prime Minister José María Aznar’s Partido Popular was defeated. The PP leaders claimed evidence indicating the Basque separatist organisation ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna) was responsible for the bombings, while the opposition claimed that the PP was trying to prevent the public from knowing it had been an Islamist attack, which would be interpreted as the direct result of Spain's involvement in Iraq, an unpopular war which the government had entered without the approval of the Spanish Parliament.

The scale and precise planning of the attacks reactivated memories of the September 11 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York (9-11).

Following the Madrid attacks, there were nationwide demonstrations and protests demanding that the government "tell the truth."

The prevailing opinion of political analysts is that the Aznar administration lost the general elections because of the handling and representation of the terrorist attacks, rather than because of the bombings per se.

Diary of an atrocity

During the peak of Madrid rush hour on the morning of Thursday, 11 March 2004, ten explosions occurred aboard four commuter trains (cercanías).

The date, 11 March, led to the abbreviation of the incident as "11-M".

All the affected trains were travelling on the same line and in the same direction between Alcalá de Henares and Atocha station in Madrid.

It was later reported that thirteen improvised explosive devices (IEDs) had been placed on the trains. Bomb disposal teams (TEDAX) arriving at the scenes of the explosions detonated two of the remaining three IEDs in controlled explosions, but the third was not found until later in the evening, having been stored inadvertently with luggage taken from one of the trains.

The following timeline of events comes from the judicial investigation.

All four trains had departed the Alcalá de Henares station between 07:01 and 07:14. The explosions took place between 07:37 and 07:40.

At 08:00, emergency relief workers began arriving at the scenes of the bombings. The police reported numerous victims and spoke of 50 wounded and several dead.

By 08:30 the emergency ambulance service, SAMUR (Servicio de Asistencia Municipal de Urgencia y Rescate), had set up a field hospital at the Daoiz y Velarde sports facility.

Later the death toll had risen to 193 confirmed dead victims, and around 2,050 injured.

Personal recollections

I vividly remember that morning.

I was in the middle of a residential education conference at Haydock Park Racecourse on Merseyside. On the morning of the bombings, I had just had breakfast when news of the atrocity broke.

In the course of watching the TV news and reading about it online, I broke down. I was weeping uncontrollably. Why?

A kindly primary headteacher I knew well asked me what was up. I told him. I was distraught. I couldn’t explain my reaction, other than that I had had a close relationship with Spain over many years, had been to Madrid a few times and knew the main station Atocha.

It was all a bit too close to home.

He advised me to pull out of the conference and go home, which is what I did, eventually.

I attended the first session of the day, but couldn’t concentrate, so took my leave at the coffee break.

With hindsight I’d had a nervous breakdown and the following week was sent on gardening leave with full pay.

There was turmoil within the education department I worked for (Sefton Council) and, fully unconnected with my breakdown, by Easter of the following year, I had been made redundant along with half a dozen other schools advisers and we were offered early retirement with access to our work pensions.

11-M aftermath

Back to the 11-M bombings in Madrid, the culprits were identified as Jihadi sympathisers, who, when discovered in an apartment building in a suburb of Madrid, blew themselves up.

Later, other co-conspirators were identified, tried in court and gaoled.

So, today is a poignant anniversary. There has been blanket coverage in the Spanish Press, on TV and online, yet no coverage whatsoever on BBC News nor ITV's Good Morning. I am disgusted.

As for me it's an event I shall never forget.

© The History Man

Acknowledgements:

ABC

At the Races

Diario Sur

El Diario

Paul Whitelock

Racecourse hospitality

RTVE

Wikipedia

Tags:

9-11, 11-M, 11 March 2004, Alcalá de Henares, Atocha, bomb disposal, bombings, cercanías, Daoiz y Velarde, Diario Sur, early retirement, gardening leave, Haydock Racecourse, History Man, IEDs, improvised explosive devices, Iraq, Jihadi, José María Aznar, Lockerbie, Madrid, Merseyside, nervous breakdown, PP, PSOE, Paul Whitelock, prime minister, redundant, SAMUR, Sefton Council, Servicio de Asistencia Municipal de Urgencia y Rescate, TEDAX, Wikipedia

***

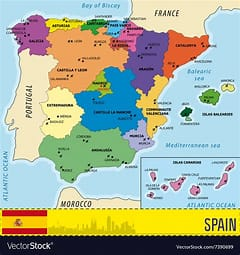

A simple introduction to the political system in Spain

Thursday, May 4, 2023

By The History Man

Spain is classified as a democratic constitutional monarchy. This means that the ruling monarch acts as the largely ceremonial head of state. The democratically elected prime minister, meanwhile, acts as the head of the national government.

The former king, Juan Carlos I

The current political system in Spain has been in place since La Transición. This was a period in the late 1970s that saw the country transition from dictatorship to democracy under the former king, Juan Carlos I, after decades of General Francisco Franco’s military rule.

This transition involved the enactment of the Spanish constitution in 1978. This serves as the framework for the current national and regional political systems.

The current head of state is King Felipe VI, who came to the throne in 2014 following the abdication of his father, Juan Carlos.

King Felipe VI

The current leader of the national government is Pedro Sánchez, head of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE). He became Prime Minister in June 2018 as the head of a coalition government.

Political parties in Spain

There are a number of political parties in Spain, and many of them operate at national, regional, and local levels. Here is a brief overview of the main political parties in Spain:

- Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE): Founded in 1879 and known as the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party in English, PSOE is the oldest party currently active in Spain. It has been in government longer than any other political party in modern democratic Spain. The party has a largely progressive ideology. It is led by Pedro Sánchez.

- Partido Popular (PP): Formed back in 1976 by Manuel Fraga Iribarne, a Spanish professor and politician under Franco’s dictatorship, the People's Party(in English) has a liberal-conservative, Christian-democratic ideology. The party was in power until 2018 and is currently in opposition and led by Alberto Nuñez Feijoo.

- Unidas Podemos (UP): This alliance of smaller progressive parties was created in the run-up to the 2016 general election. These include Podemos, Izquierda Unida, and other smaller parties. The party has been in the governing coalition with PSOE since the 2020 general election. UP is currently led by Yolanda Díaz Pérez.

- Ciudadanos (Cs): Known as Citizens in English, this party came into being in Catalonia back in 2006. It is a liberal-conservative, pro-European party. Since then, Ciudadanos‘ fortunes have varied significantly. The current party president is Inés Arrimadas.

- Vox: Former members of the Partido Popular founded this anti-immigration, nationalist party in 2013. It has risen in popularity over recent elections, both on a national and regional level. Vox is led by Santiago Abascal.

[The above section requires an update, in light of changes in 2023].

Regional politics in Spain

Spain is divided into 17 autonomous regions, which are self-governing entities with their own powers and responsibilities. Each region consists of one or more provinces, except for seven regions that are uniprovincial, meaning they have only one province each. Some regions also have special status, such as the Canary Islands and the Basque Country, which have more autonomy than others.

Local politics in Spain

Local government in Spain operates at the municipal level, with residents electing local councillors who then choose a mayor (alcalde). The mayor then appoints a board of governors for the local municipality. In Spain, local municipalities are responsible for the local police, traffic policy, urban planning, social services, and certain taxes.

With thanks to www.expatica.com

***

Spanish Prime Ministers since Franco

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

By The History Man

Following the death of General Francisco Franco Bahamonde in 1975, the incumbent prime minister Carlos Arias Navarro remained in post for 209 days until Adolfo Suarez was elected in the first democratic elections under the new Constitution.

To read the complete article click on the link below:

Spanish Prime Ministers since Franco (eyeonspain.com)

***

A Failed Coup

Friday, December 29, 2023

By The History Man

As we move into 2024 an attack on democracy is taking place in the Ukraine, as Russian president Vladimir "hijo de" Putin seeks to become the greatest ever war criminal in the history of the world.

We should remember that almost 43 years ago there was another attack on democracy in a European country - the newly democratic Spain.

Photo: The Guardian

On 23 February 1981 Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero, an officer of the Guardia Civil, entered the Spanish parliament, Las Cortes, waving a loaded pistol aloft, and proceeded to hold the members of parliament hostage.

The History Man recalls the day 40 years ago when the newly-fashioned democratic Spanish state came under threat once again from the military, as it had done in 1936, prior to the Civil War.

Parliament stormed

Shots were being fired in the Spanish parliament. Live camera images on television showed a lone figure in a tricorn hat taking control of the chamber.

He was then joined by other armed men in uniform with machine guns. More than 37 shots were fired as delegates dived for cover.

Photo: The Boston Globe

It later transpired that Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero had been supported by 200 armed civil guards and soldiers.

The 23 February 1981 Spanish coup d’état attempt (Spanish: Intento de Golpe de Estado de España de 1981) was an attempted military takeover of the elected government.

Tejero led 200 armed Civil Guard officers into the Congress of Deputies during the vote to elect a President of the Government. The officers held the parliamentarians and ministers hostage for some 22 hours, during which time King Juan Carlos I denounced the coup in a televised address, calling for rule of law and the democratic government to continue.

The following day, coup leaders surrendered to the police.

Tejero made the following statement: “We received a country in perfect condition; we are obliged to hand it to our offspring in the same condition.”

Though shots were fired, the hostage-takers did not kill anyone.

Background

The coup attempt was linked to the Spanish transition to democracy. Four factors generated tensions that the governing Democratic Centre Union (UCD) coalition of conservative parties could not contain:

- almost 20% unemployment, capital flight and 16% inflation caused by an economic crisis,

- difficulty devolving governance to Spanish regions,

- increased violence by the Basque terrorist group ETA,

- opposition to the fledgling democracy from within the Spanish Armed Forces.

The first signs of unease in the army appeared in April 1977. Admiral Pita da Veiga resigned as Navy minister and formed the Superior Council of the Army. This was a result of Da Veiga’s disagreement with the legalisation of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) on 9 April 1977, following the Atocha massacre by neo-fascist terrorists.

In November 1978, the Operation Galaxia military putsch was put down. Its leader, the very same Lieutenant-Colonel Antonio Tejero, was sentenced to seven months in prison.

Photo: Wikipedia

While seditious sentiments grew in sectors of the military and extreme right, the government faced a serious crisis at the beginning of the decade, and its position became increasingly untenable in the course of 1980.

The growing weakness of Adolfo Suárez at the heart of his own party led to his televised resignation as prime minister and president of the UCD on 29 January 1981.

On 1 February, the “Almendros Collective” published an openly insurgent article in the far-right newspaper El Alcázar, which was the mouthpiece of the Búnker hardliners, including Carlos Arias Navarro, Luis Carrero Blanco’s successor as prime minister, and the leader of the francoist party Fuerza Nueva, Blas Piñar.

From 2 to 4 February, the King and Queen travelled to Guernica, where the deputies of Basque separatist party Herri Batasuna received them with boos and hisses and various incidents.

In this atmosphere of mounting tension, the process of choosing Suárez’s successor began. Between 6 and 9 February, the 2nd UCD congress in Majorca made it clear that the party was unravelling and Agustín Rodríguez Sahagún was named acting prime minister.

On 10 February, Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo was named candidate for prime minister.

On the day of the assault on Congress several TVE cameramen and technicians filmed almost half an hour of the event, providing the world with an audiovisual record of the attempted coup (which would be broadcast several hours after it ended).

Moreover, members of the private radio station SER continued their live broadcast with open microphones from within the Congress of Deputies, which meant that the general public was able to follow along by radio as events unfolded.

As such, the date is sometimes remembered as “the Night of Transistor Radios”(La noche de los transistores).

At 18:00, the roll-call vote for the swearing in (investidura) of Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo as prime minister began in the Congress of Deputies.

At 18:23, as Socialist-party deputy Manuel Núñez Encabo was standing up to cast his vote, 200 Guardia Civil agents led by Lieutenant-Colonel Antonio Tejero and armed with submachine guns, burst into the congressional chambers. Tejero immediately took the Speaker’s platform and shouted “¡Quieto todo el mundo!” (“Nobody move!”), ordering everyone to lie down on the floor.

As the highest-ranking military official present, Army General (and Deputy Prime Minister) Manuel Gutiérrez Mellado refused to comply, confronting Tejero and ordering him to stand down and hand over the weapon.

Adolfo Suárez [Photo: HOLA]

Outgoing Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez made a move to join Gutiérrez Mellado, who briefly scuffled with several civil guards until Tejero fired a shot into the air, which was followed by a sustained burst of submachine-gun fire from the assailants. (The shots wounded some of the visitors in the chamber’s upper gallery).

Undeterred, arms akimbo in defiance, 68-year-old General Gutiérrez Mellado refused to sit down, even after Tejero attempted, unsuccessfully, to wrestle him to the floor.

Their face-off ended with Tejero returning to the rostrum and Gutiérrez Mellado returning to his seat.

After several minutes, all the Deputies retook their assigned congressional seats. The captain of the Guardia Civil, Jesús Muñecas Aguilar, strode to the Speaker’s platform, demanded silence and announced that all those present were to wait for the arrival of “the competent military authority.”

At 19:35, prime minister Suárez stood up and asked to speak to the commanders. Shots were fired in response, and a guard flashed a submachine gun towards the deputies’ seats, demanding silence.

One of the assailants ordered, “Mr. Suárez, stay in your seat!” Suárez was about to reply when someone else shouted, “Se siente, coño!” (“Sit down, damn it!”)

Finally, Tejero grabbed Suárez by the arm and led him forcefully to a room outside the chamber. When Suárez demanded that Tejero explain “this madness”; Tejero‘s only reply was “¡todo por España!” (“Everything for Spain!”).

When Suárez pressed the point, citing his authority as prime minister (“president of the government”), Tejero replied, “Tú ya no eres presidente de nada!” (“You are no longer the president of anything!”)

Military occupation of Valencia

A simultaneous rebellion in eastern Spain fizzled out. Shortly after Tejero took control of the Congress, Jaime Milans del Bosch, Captain General of the III Military Region, executed his part of the coup in Valencia.

Leading figures in the attempted coup [Photo: El Cierre Digital]

Deploying 2,000 men and fifty tanks from his Motorized Division as well as troops from the port of Valencia onto the streets and into the city centre, they occupied the Town Hall (Ayuntamiento) and the Valencian judicial court building (Las cortes valencianas).

The revolt, known as Operation Turia, was considered key if other military regions were to become involved in the coup. By 19:00, Valencian radio stations began broadcasting the state of emergency declared by Milans del Bosch, who was hoping to convince others to endorse his military action.

Well into the night, Valencia was surrounded by armoured military trucks and other troop units called in from the Bétera and Paterna army bases. Police snipers took their places on rooftops, military marches were played on loudspeakers and a curfew was imposed on the citizens.

An armoured convoy was dispatched to the Manises Air Base in order to convince the commander there to support the coup; however, the Colonel of the 11th Wing in charge of the base not only refused to comply, he threatened to deploy two fighter jets armed with air-to-ground missiles (which he claimed to have standing by with their engines running) against the tanks sent by Milans del Bosch, thereby forcing the latter to withdraw.

This setback hinted the impending failure of the Madrid coup.

Juan Carlos’s repudiation

King Juan Carlos refused to endorse the coup. The monarch, after protracted discussions with colleagues, was convinced of his military leaders’ loyalty to himself and the Constitution.

Two and a half hours after the seizure Juan Carlos phoned the president of the Government of Catalonia Jordi Pujol and assured him that everything was under control.

Jordi Pujol at the time of the coup [Photo: Wikipedia]

Pujol, just before 22:00 that evening, made a short speech via national broadcasting stations inside and outside of Spain calling for peace.

Until 1:00 in the morning (24 February), negotiations took place outside the Congress between the acting government as well as General Alfonso Armada, who would later be relieved of his duties under suspicion that he had participated in planning the coup.

At 1:14 on 24 February, the King of Spain appeared live on television, wearing the uniform of the Captain General of the Armed Forces (Capitán General de los Ejércitos), the highest Spanish military rank, to oppose the coup and its instigators, defend the Spanish Constitution and disavow the authority of Milans del Bosch.

King Juan Carlos I addresses the nation on TV [Photo: La Vanguardia]

The King declared: “I address the Spanish people with brevity and concision: In the face of these exceptional circumstances, I ask for your serenity and trust, and I hereby inform you that I have given the Captains General of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force the following order: 'Given the events taking place in the Palace of Congress, and to avoid any possible confusion, I hereby confirm that I have ordered the Civil Authorities and the Joint Chiefs of Staff to take any and all necessary measures to uphold constitutional order within the limits of the law.'

'Should any measure of a military nature need to be taken, it must be approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.' The Crown, symbol of the permanence and unity of the nation, will not tolerate, in any degree whatsoever, the actions or behaviour of anyone attempting, through use of force, to interrupt the democratic process of the Constitution, which the Spanish People approved by vote in a referendum.”

From that moment on, the coup was understood to be a failure. Deputy Javier Solana stated that when he saw Tejero reading a special edition of the El País newspaper brought in by General Sáenz de Santamaría, which vehemently condemned the hostage situation inside the Congress, he knew that the coup had failed.

For his part, Milans del Bosch, alone and thereafter isolated, abandoned his plans at 5:00 that morning and was arrested.

The deputies were freed that morning after emerging one by one from their all-night ordeal shouting “Long Live Freedom”.

Tejero resisted until midday on 24 February and was arrested outside the Congress building.

The Guardian newspaper

Legacy

The most immediate consequence was that, as an institution, the Monarchy emerged from the failed coup with overwhelming legitimacy in the eyes of the public and the political class.

In the long term, the coup’s failure could be considered the last serious attempt by adherents to Francoist ideology to destroy Spain’s future as a democracy and implement their fascist totalitarian designs on the nation.

The Supreme Court of Military Justice, known as the Campamento trial (juicio de Campamento), condemned Miláns del Bosch, Alfonso Armada and Antonio Tejero to thirty years in prison as the key instigators of the coup d’état.

Eventually, thirty people out of some 300 accused would be convicted for their involvement in the coup.

With acknowledgements to Wikipedia

***

The Rise and Fall of King Juan Carlos I

Saturday, March 5, 2022

By The History Man

Juan Carlos I with his queen Sofia (Photo: The Telegraph)

When Juan Carlos I succeeded Francisco Franco as Head of State on the Generalissimo’s death in November 1975 the King played a major role in moving Spain from a right-wing dictatorship to a modern democratic constitutional monarchy.

However, over the years a number of controversies led to his abdication in 2014 and since then a long list of allegations of corruption have emerged. This led to him going into self-imposed exile in the United Arab Emirates in 2020.

The recent court trial of the former king has just ended. The case has been archivado, filed away. In other words no further action is to be taken. He is free to go.

The History Man plots the rise and fall of this once extremely popular monarch.

Background

Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón was born on 5 January 1938. He is the grandson of Alfonso XIII, the last king of Spain before the abolition of the monarchy in 1931 and the subsequent declaration of the Second Spanish Republic.

Juan Carlos was born in Rome during the royal family’s exile and grew up in Italy.

Francisco Franco took over the government of Spain after his victory in the Spanish Civil War in 1939, yet in 1947 Spain’s status as a monarchy was affirmed and a law was passed allowing Franco to choose his successor.

He by-passed Juan Carlos’s father, Juan, the third son of King Alfonso, who had renounced his claims to the throne in January 1941, as Franco considered him to be too liberal, and in 1969 installed Juan Carlos as his successor as head of state.

Coronation [Photo courtesy of Town and Country Magazine]

On Franco’s death in 1975, Juan Carlos became king and reigned until his abdication in June 2014.

In Spain, since his abdication, Juan Carlos has usually been referred to as the Rey Emérito, King Emeritus.

Juan Carlos spent his early years in Italy and came to Spain in 1947 to continue his studies. After completing his secondary education in 1955, he began his military training and entered the General Military Academy at Zaragoza. Later, he attended the Naval Military School and the General Academy of the Air, and finished his tertiary education at the University of Madrid.

In 1962, Juan Carlos married Princess Sophia of Greece and Denmark in Athens. The couple had two daughters and a son together: Elena, Cristina, and Felipe.

Due to Franco’s declining health, Juan Carlos first began periodically acting as Spain’s head of state in the summer of 1974. Franco died in November the following year and Juan Carlos became King on 22 November 1975, two days after Franco’s death, the first reigning monarch since 1931; although his exiled father did not formally renounce his claims to the throne in favour of his son until 1977.

Juan Carlos was expected to continue Franco’s legacy, which is why Franco chose him to be his successor. The new king, however, had other ideas and soon after his accession introduced reforms to dismantle the Francoist regime and begin the Spanish transition to democracy.

This led to the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978 in a referendum which re-established a constitutional monarchy.

In 1981, Juan Carlos played a major role in preventing a coup that attempted to revert Spain to Francoist government in the King’s name.

In 2008, he was considered the most popular leader in all Ibero-America. He was praised for his role in Spain’s transition to democracy.

According to a poll in the newspaper El Mundo in November 2005, 77.5% of Spaniards thought Juan Carlos was “good or very good”, 15.4% “not so good”, and only 7.1% “bad or very bad”.

Emerging controversies

However, the King and the monarchy’s reputation began to suffer after controversies arose surrounding his family, exacerbated by the public controversy centring on an elephant-hunting trip he undertook to Botswana during a time of financial crisis in Spain. Up until the Botswana elephant trip, Juan Carlos had enjoyed a high level of shielding from media scrutiny, described as “rare among Western leaders”.

Spanish news media speculated about the King’s future in early 2014, following public criticism over the Botswana trip and an embezzlement scandal involving his daughter Cristina, and her husband Iñaki Urdangarin.

Abdication

In June 2014, citing personal reasons, Juan Carlos I abdicated in favour of his son, who acceded to the throne as Felipe VI.

Felipe VI [Photo courtesy of Alamy]

The Spanish constitution at the time of the abdication did not grant an abdicated monarch the legal immunity of a head of state, but the government changed the law to allow this. However, unlike his previous immunity, the new legislation left him accountable to the supreme court, in a similar type of protection afforded to many high-ranking civil servants and politicians in Spain.

The legislation stipulates that all outstanding legal matters relating to the former king be suspended and passed “immediately” to the supreme court.

In June 2019, the former King announced his retirement from all official duties.

Recordings of the former King’s alleged mistress Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn speaking with a former police chief, were leaked to the press in mid-2018. Sayn-Wittgenstein claimed that Juan Carlos received kickbacks from commercial contracts in the Gulf States and that he maintained these proceeds in a bank account in Switzerland.

Former mistress Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn [Photo: Lecturas]

She alleged that he purchased properties in Monaco under her name to circumvent the tax treatment of lawful residents, stating “[not] because he [loved] me a lot, but because I reside in Monaco.” She further claimed the head of the Spanish intelligence service warned her that her life, and those of her children, would be at risk if she spoke of their association.

Investigation into Corruption

The allegations drew demands for Juan Carlos to be investigated for corruption in early June 2019.

Swiss authorities began investigating Juan Carlos in March 2020. Sayn-Wittgenstein reportedly told the head Swiss prosecutor on 19 December 2018 that Juan Carlos had gifted her €65 million out of “gratitude and love”, to guarantee her future and her children’s, because “he still had hopes to win her back”. A letter written by Juan Carlos to his Swiss lawyers in 2018 stated the gift was irrevocable, despite having asked in 2014 for the return of the money.

On 14 March 2020, The Telegraph reported that his son Felipe, King of Spain since 2014, appeared as second beneficiary (after Juan Carlos) of the Lucum Foundation, the entity on the receiving end of a €65 million donation by Abdullah bin Abdulaziz, King of Saudi Arabia.

On 15 March 2020, the Royal Household issued a statement declaring that Felipe VI would renounce any inheritance from his father. Additionally, the statement announced that the former king would lose his public stipend from the State’s General Budget.

Felipe and Juan Carlos at odds [Photo: Diario Publico]

In June 2020, the public prosecutor’s office of the Spanish Supreme Court accepted to pursue an investigation against Juan Carlos pertaining to his role as facilitator in Phase II of the high-speed rail connecting Mecca and Medina, intending to delimitate the criminal relevance of the facts that took place after his abdication in June 2014.

As King of Spain, Juan Carlos was immune from prosecution from 1975 to 2014 via crown immunity.

A further investigation by Swiss authorities is being undertaken regarding €3.5 million paid from the Lucum Foundation to the Bahamas-based bank Pictet & Ciein for a society called Dolphin, which was controlled by the lawyer Dante Canónica, who also controlled Lucum.

Spanish prosecutors opened an investigation into the use by Juan Carlos and other members of the royal family of credit cards between 2016 and 2018 which were paid for by an overseas account to which neither Juan Carlos nor any member of the royal family were signatories. This led to accusations that the funds are undisclosed assets of Juan Carlos, and as the card drawings exceeded €120,000 in one year, comprised undisclosed income and was therefore a tax offence in Spain.

Mexican millionaire and investment banker Allen Sanginés-Krause has been named as the owner of the cards, a friend of Juan Carlos to whom he donated sums of money using Air Force Colonel Nicolás Murga Mendoza as an intermediary.

Photo: El Confidencial

In December 2020, Juan Carlos reportedly paid 678,393.72 euros to Spain’s tax agency for the concept of defrauded money in an affair of “opaque credit cards” used between 2016 and 2018 by himself, his wife and some grandchildren, intending to avoid further scrutiny from the Supreme Court’s prosecutor, the payment being, in fact, an admission of fraud.

A third investigation is being undertaken by the Spanish authorities over an attempt to withdraw nearly €10 million from Jersey, possibly from a trust set up by or for Juan Carlos in the 1990s.

Juan Carlos claims he is “not responsible for any Jersey trust and never has been, either directly or indirectly.”

A further investigation is taking place regarding the fact that until August 2018 Juan Carlos maintained a bank account in Switzerland which contains almost €8 million.

Reports have been made that Juan Carlos made a private trip to Kazakhstan in October 2002 to hunt goats with President Nursultan Nazarbayev. On departure from Kazakhstan he was given 4 to 5 briefcases purportedly containing $5 million in cash.

The Zagatka Foundation, founded in Liechtenstein in 2003 and owned by Álvaro de Orleans-Borbón, a distant cousin of Juan Carlos who lives in Monaco, received a large sum of money from Switzerland. Juan Carlos is named as the third beneficiary.

In 2009 Álvaro de Orleans-Borbón paid a cheque from Mexico for €4.3 million into the account which the Swiss adjudicated belonged to Juan Carlos.

Juan Carlos appears to have drawn down funds from the Zagatka Foundation to spend €8 million between 2009 and 2018 on private flights, with Air Partner receiving around €6.1 million.

Image courtesy of Przedszkole Zagadka

Zagatka used commissions due to Juan Carlos and paid to Zagatka to invest millions, mainly in Ibex35 companies between 2003 and 2018.

A Panamanian Lucum foundation had Juan Carlos as the first beneficiary and King Felipe VI as a named second beneficiary, although King Felipe VI has subsequently relinquished any inheritance from his father Juan Carlos.

Lucum received $100 million from the Saudi royal house in 2008. Swiss prosecutors are concerned about who at the Swiss bank, Mirabaud & Cie, know who the account was for and what was discovered about the source of funds from the Ministry of Finance of Saudi Arabia. They are also concerned about a €3.5m transfer from Lucum to the Bahamas to an account held by Dante Canónica.

Mirabaud bank, who had concealed from its employees the beneficial owner of the account, asked in 2012 for the account to be closed, due to possible adverse publicity, this was when the bulk of the funds were transferred to Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn.

On 3 August 2020, the Zarzuela Palace announced Juan Carlos wished to relocate from Spain because of increased media pressure about his business dealings in Saudi Arabia.

Since then, Juan Carlos has lived in self-exile from Spain over allegedly improper ties to business deals in Saudi Arabia.

On 17 August, the Royal Household confirmed that, since 3 August, Juan Carlos has been living in the United Arab Emirates, where he arrived by taking a private plane from Vigo Airport.

Private Life

As for his private life, this too is not without controversy. Juan Carlos and Sofía have had two daughters and one son, but they have apparently not shared a bed since 1975.

Juan Carlos and Sofia separate

Juan Carlos is also the alleged father of Alberto Sola, born in Barcelona in 1956, also of an unnamed woman born in Catalonia in 1964, and of Ingrid Sartiau, a Belgian woman born in 1966 who has filed a paternity suit, but complete sovereign immunity prevented that suit prior to his abdication.

Juan Carlos had several extramarital affairs adversely affecting his marriage, including on ongoing relationship with Diana, Princess of Wales, who, along with Prince Charles, spent every summer as guests of the King in Mallorca.

So, Juan Carlos has truly gone from hero to zero over the course of three decades and his legacy will be forever tainted.

What a great shame!

Additional reading

THE GUARDIAN: Former Spanish king’s ex-lover says she was threatened by spy chief

Corinna Larsen tells court ‘chilling’ warning to her and her children came on the orders of King Juan Carlos…